With the global temperature expected to increase by 1.5 degrees Celsius in the next two decades, the world needs to take “immediate, rapid and large-scale” actions in reducing greenhouse gases. And to investors and observers, carbon trading schemes may be the silver bullet. The World Bank’s annual report pointed out that there are 64 carbon pricing instruments worldwide, covering 21% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Its USD35-billion revenue can affirm the potential of this market-based solution to a global environmental challenge.

Yet, in reality, carbon traders face a dilemma. While originally a means to curb carbon emission, carbon trading has virtually become a mere business. So instead of helping the world reduce carbon, the schemes may have only benefited investors and financiers. Can carbon trading’s original intention still hold?

What is carbon trading?

The end goal for carbon trading is to gradually reduce the world’s carbon footprint and mitigate the effects of climate change © Nick Fewings / AvantFaire

Carbon trading is a market-based system aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow global warming. It originated from the Kyoto Protocol in 2005 as a global effort to cut down carbon emissions. Governments worldwide issue and maintain their overall limits of carbon dioxide emission, within which entities can trade for the rights for a certain amount of emission. The end goal is to gradually reduce the world’s carbon footprint and mitigate the effects of climate change.

Instead of resorting to hard regulations and unpopular carbon taxes, carbon trading lets companies sell the rights to emit and the option to buy extra emission quotas. Wealthier entities would subsidise developing countries by buying their credits, and with advancing technology and joint emission caps across regions, all countries would theoretically emit less carbon altogether.

While the original Protocol delivered mixed results, carbon trading schemes remained favourable. Recently, China initiated a national emission-trading programme in July 2021. Starting with 2,225 companies in the power sector, this programme will make China the world’s largest carbon market and help the country achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Meanwhile, the EU has adopted a series of legislations to refine its emission-trading system (ETS), helping it achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. It will increase the annual cap reduction while ensuring free allocation of credits and innovations for a low-carbon future are in place.

A report from McKinsey summarised the advantages of carbon trading into two points. First, it allows companies to decarbonise beyond their carbon footprint to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon future across borders and sectors. Second, it helps finance carbon-removing projects and eventually makes negative emissions possible, which is essential for neutralising residual emissions accumulated from years of intense industrialisation.

Expectations vs reality

Is our carbon footprint getting smaller? © Maxim Tolchinskiy / AvantFaire

Despite its promising prospects, carbon trading has its limitations. Though the ultimate goal for this scheme is to cap, leverage and reduce carbon emission, empirical figures have apparently revealed that the overall picture is more complex than what investors may expect. In fact, there are a few dilemmas that the carbon market needs to solve to make carbon trading effective and meaningful.

Favour tilted towards big players

Theoretically, in a truly inclusive, or Coasean, scenario, all stakeholders such as communities exposed to emissions should have a say in the carbon price bargaining. Yet, factors like ability to pay, collection problems, and a lack of consensus among smaller players have undermined their ability to act and safeguard their bottom lines. Moreover, carbon trading poses a moral hazard, that large carbon-trading corporations could essentially pay their way out of their ethical obligation of mitigating global warming. While carbon trading, at least theoretically, could help offset the world’s overall emissions, the damage from extreme weather events such as natural disasters and loss of life cannot be translated into monetary terms.

One may also argue that carbon trading is a neoclassical example of the imbalance between the industrialised states and the Global South that bear the larger brunt of climate change. At least right now, carbon trading has done little in alleviating the problems plaguing the Global South and everyday communities worldwide. Instead, it is widening the inequality gaps that have already existed. By reducing the discussion to only carbon and money, the current carbon market is too simplistic to target public problems like community, equality and labour.

Price unsustainability

The carbon market faces a Goldilocks problem. With carbon emissions gradually dropping, institutions needed to issue enough buy signals and induce scarcity to maintain demand. But as carbon trading becomes profitable and price-attractive, it will attract the attention of speculators, further spiking carbon prices up and adversely affecting different countries’ economic plans. Getting the balance right is not only an economic problem but also a political one, and it is harder than it looks.

After the EU cleared out much of its emission permit oversupply and cut its 2030 emission target from 40% to 55%, carbon prices in the ETS rose though emission levels were falling. Despite the EU’s some 11,000 carbon-emitting companies are still in the centre of the EU’s ETS, the price spike has caught the attention of investment companies, increasing their long position presence from 4% in 2020 to 7% in 2021.

As of 24 September 2021, carbon emission at the EU’s ETS has priced carbon emission at EUR62.94 per tonne, a dramatic increase from EUR34 in January. Experts believe factors like high gas prices, the 2018 ETS reform and decreased supply of CO2 have caused the dramatic price increase, and expect that new entrants, increasing speculation and increasing market volatility will drive the price to EUR90 by 2030.

Yet, a paradox has emerged. If carbon prices are expected to rise, emitters and speculators will load up to maintain the bottom line. But by doing so, not only will the focus shift towards profiteering rather than curbing emissions, countries lagging in decarbonising will find it even harder to run their economies and emission-reducing efforts. Some experts argue that to effectively incentivise a reduction of emissions, carbon prices need to go even higher, reaching USD140 per tonne for advanced countries. European Greens have even urged for EUR150 to “curb free-riders”. This drastic spike may create tension in the political economy sense, as coal-dependent countries like Spain and Poland have already voiced their difficulties when emission prices reached EUR60 earlier this year. “If you want to hinder an explosion in carbon prices, what you can do is support your industry in the decarbonisation pathway,” said Florian Rothenberg, a market analyst at ICIS.

Coasean setbacks and demand inelasticity

A Coasean answer to a decarbonisation pathway would be to consider all emission sources. While it is fairer and more inclusive, accounting all carbon emissions into the price mechanism will certainly create inflationary pressure on all global production and supply chain activities as the risk cost will be passed on to all major sectors across the global economy, from supply chain, manufacturing to even import-export. This phenomenon will almost certainly incur currency inflation and undermine export capabilities among trade-rich countries. Since it is still yet to be proven whether renewable energy could fully replace fossil fuels in the near future, and given the inelastic demand for energy from human activities, a Coasean scenario would ironically spike up fossil fuel prices and create multiplier effects that are adverse and unpredictable.

Taking all carbon emissions into account may create unexpected consequences © Pixabay / AvantFaire

Currently, established first-movers can leverage ways to reduce their carbon market risks through risk trading and operational changes. But that can all change if all emissions are considered wholesale. A report from a European think tank may provide a hint. It suggested that the EU’s CBAM initiative, due to its complexity and difficulties to cater to all member states and entities, may face a “first-mover disadvantage”. The EU’s ambitious Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), an extension of its ETS, is a notable example. CBAM essentially imposes costs on imports on some carbon-intensive products as a means to intensify the EU’s push for carbon-neutrality by 2050. Under CBAM, foreign importers for iron and steel, cement, fertilisers, and aluminium must purchase emission certificates based on their emission levels.

Besides some member states, foreign trading partners have borne much of the brunt of the ETS, affecting countries ranging from Russia to Ukraine, South Korea, and even Colombia and Mozambique. In April 2021, Brazil, China, India and South Africa expressed grave concern over the scheme, of which they considered a unilateral trade barrier. Also, any affected countries could challenge the CBAM at the World Trade Organization, which would incur legal and political troubles.

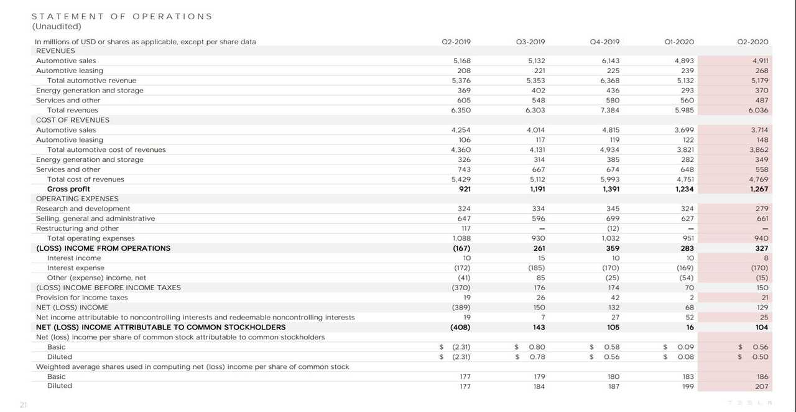

Case study: Tesla

Even at a company level, carbon trading can bring its fair share of promises and headaches. Carbon trading has been essential to Tesla’s profit. In Q1 2021, carbon trading has hit a record earning level of USD518 million. While only accounting for 6% of the overall revenue, Tesla would not have been profitable on a net basis without it. By relying on carbon trading schemes so significantly on its liquidity, Tesla’s profitability is in a vulnerable position. In Q2 2020, Tesla received USD428 million from trading carbon certificates. Still, when juxtaposed with its USD418 million positive cash flow and USD104 million net profit, the manufacturer may face a liquidity issue without carbon trading.

Tesla’s profitability once relied upon carbon trading © Tesla / AvantFaire

When Fortune reported that Tesla was potentially losing a crucial revenue stream after one of its suppliers decided to wind down its purchase of the electric car brand’s carbon emission certificates, it did show Tesla was in a rather compromising position. In fact, Tesla did experience a negative cash flow of USD895 million in Q1 2020 as its car manufacturing business faces limited profitability. Nonetheless, Tesla’sTesla’s Q2 2021 revenue showed the company is gradually shedding its reliance on carbon credits, scoring USD1.6 billion in adjusted profit while revenue from carbon trading dropped 17% year to year.

A takeaway is that instead of facilitating car manufacturers to curb emissions, reliance on carbon trading has driven them to accelerate manufacture and sales to get more carbon credits. This means carbon trading may have a long way to go in fully helping the world fight global warming.

Solving the carbon dilemma

A global framework will help determine the key principles of determining the price and supply of carbon credits © Frederic Köberl / AvantFaire

If the market is to make carbon trading sustainable, it is essential to rediscover and stay true to the scheme’s true intentionality of curbing emissions. The carbon market needs to address more than mere price and emission. It needs to induce new technologies that can fundamentally change how we reduce carbon footprint while addressing the intangible problems different communities are facing. There are two ways of achieving that: by introducing the right incentives and governance.

Countries and carbon markets need to provide meaningful incentives for change. Dr. Erik Berglof, Chief Economist of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, commented in the “Renewables & Climate Change: An Overview of Carbon Market” webinar that removing fossil fuel subsidies is the first step to help major emitters to make a real change. He cited the requirements of China’s ETS market – now the largest in the world – on covered entities to invest in eco-friendly technologies, which takes one step further from mere investing and will help drive sustainable impact.

Catherine Chen, founder and CEO of AvantFaire, added that the focus should be on how fast prices should be raised, and the market itself needs to be aware of what carbon neutrality and green finance practices mean. “[Effective carbon trading] involves not only the policy settings, but also the participation of the corporates and other enterprises”, she said.

Besides setting incentives, another way to break the carbon trading dilemma is to send stable price signals to the carbon market. With that, the global carbon market needs to collaborate in creating a reliable governance mechanism, so investors and companies can operate in a vibrant and transparent carbon market that can bring returns and reduce emissions.

Pascal Saint-Amans, director of the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, argued that carbon price volatility is an obstacle to pushing green investment and green recovery, as instability would deter business involvement. Grace Hui, managing director, head of the Green and Sustainable Finance, Markets Division at Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd, echoed the sentiment. Together with a global governance body, a global framework will help determine the key principles of determining the price and supply of carbon credits, she argued.

“The different standards in the existing voluntary carbon markets make the carbon credits not fungible”, Hui said.

“We hope to be able to use standardised core carbon reference contracts together with additional attributes such as social co-benefits.”

.

.